DEDC Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Bloc Quebecois’s Complementary Report [DEDC]

First, the Bloc Québécois would like to thank the witnesses for their valuable testimony in speaking out about the occupation of Parliament Hill from January 28 to February 20, 2022, as well as the collateral events that occurred. The Committee also considered the evidence presented before the Rouleau Commission, which had made available and translated to examine the context and relevance of the Declaration of Public Order Emergency (Declaration). The state of emergency, as defined in the Emergencies Act, was in effect from February 14 to February 23, 2024.

We believe that such a report, by its importance in the citizens’ democratic life, would have deserved clear and constructive conclusions. In our view, the absence of conclusions in the present report alone justifies the submission of a supplementary report to make our own known.

As a preliminary remark, we are of the opinion that by the nature and intentions of this demonstration, it was, from the outset, an “Unlawful assembly” and the police forces could have acted much more quickly to thwart the occupation plans of the group of demonstrators. This observation seems obvious to us when we read the intelligence note prepared by the OPP and sent to the OPS before the convoy's arrival[1]. The Criminal Code is in fact quite clear and applies perfectly to the situation at hand. Article 63 paragraphs 1 and 2 clearly state that a demonstration can become an “unlawful assembly”:

“ 63 (1) An unlawful assembly is an assembly of three or more persons who, with intent to carry out any common purpose, assemble in such a manner or so conduct themselves when they are assembled as to cause persons in the neighbourhood of the assembly to fear, on reasonable grounds, that they

(a) will disturb the peace tumultuously; or

(b) will by that assembly needlessly and without reasonable cause provoke other persons to disturb the peace tumultuously.

Lawful assembly becoming unlawful

(2) Persons who are lawfully assembled may become an unlawful assembly if they conduct themselves with a common purpose in a manner that would have made the assembly unlawful if they had assembled in that manner for that purpose”[2].

The Bloc Québécois is of the opinion that not only was the Government of Canada not required to invoke the Emergencies Act, but that its decision to do so was mainly due to its chaotic and disorganized management of events. The next few paragraphs will be devoted to supporting the arguments that lead us to this conclusion.

1. THE OBLIGATION TO CONSULT AND THE DETERMINATION OF THE DESIGNATED AREA

Initially, despite the obligation under section 25 of the Emergencies Act to consult the premiers of Quebec and the provinces, the Government of Canada did not take their opinions into account. The majority of provinces, seven out of ten, were against invoking the Emergencies Act: Quebec, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia[3]. Only Ontario, British Columbia and Newfoundland and Labrador felt that the declaration of a state of emergency was necessary. In the alternative, it should be noted that the Government of Canada consulted the territorial governments, even though the Emergencies Act does not require it to do so. At the end of this exercise, even after being informed of the contrary opinions of the provinces, the federal government chose to declare a state of emergency.

This was one of the points discussed during the committee hearings. It is interesting to note that some of the testimonies included in the report were to the effect that the consultations had been inadequate, since they had been nothing more than a superficial exercise in which the opinions of the provinces had never really been considered. The federal government's justification for this was quite extraordinary: “[...] the fear of a leakage of information and the possibility that a declaration of a state of emergency could provoke the anger of demonstrators and increase the risk of violence”[4].

Leakage or not, it was obvious that the federal government's objective was to declare a state of emergency. Increased pressure from the demonstrators would, on the contrary, only have validated their decision.

In order to prevent such a circumvention of the consultation objectives in the future, the Bloc Québécois recommends that section 25 of the Emergencies Act be amended to require the Governor-in-Council to justify his decision to override the advice of his counterparts. These reasons must be included in the declaration provided for in section 17 of this Act.

Secondly, the decision to impose a state of emergency on the entire territory was, in our opinion, equally unjustified, especially since paragraph 17(2)(c) of the Emergencies Act precisely allows the government to limit the application of the state of emergency to a specific territory.

The very purpose of this provision is to avoid unreasonable infringement of individual rights and freedoms. The federal government, in its haphazard and chaotic management of the crisis, took the easy way out by applying the proclamation to the entire territory, not just specific locations. Moreover, the Federal Court supports our reasoning in a judgment on the matter handed down on January 29, 2024, stating that :

“Section 17(2)(c) of the Act requires that if the effects of the emergency did not extend to the whole of Canada, the area of Canada to which it did extend shall be specified. While the word “area” in the legislative text is singular, per section 33(2) of the Interpretation Act that includes the plural. Thus, it was open to the GIC to specify several or many areas that were affected by the emergency excluding others where the situation had not arisen or was under control. However, the Proclamation stated that it “exists throughout Canada”. This was, in my view, an overstatement of the situation known to the Government at that time. Moreover, in the first reason provided for the proclamation, which referenced the risk of threats or use of serious violence, language taken from section 2 of the CSIS Act, the emergency was vaguely described as happening at “various locations throughout Canada”.”[5]

The Bloc Québécois therefore shares Justice Mosley's opinion and disagrees with the federal government's decision to impose such a broadly territorial declaration of a state of emergency.

Therefore, in order to better protect citizens from unjustified interventions by the federal government on their territory, the Bloc Québécois recommends that the Governor-in-Council be required to justify his decision to designate the zone in which the Emergencies Act will be applied, whether pan-Canadian or more circumscribed.

- 2. EXISTING LEGISLATION, REGLEMENTATION AND POWERS

Secondly, according to the many testimonies heard, there were still means within the ordinary body of legislation to contain the crisis when the federal government declared a state of emergency. Last January, the Federal Court agreed, stating as follows:

“[…] While I agree that the evidence supports the conclusion that the situation was critical and required an urgent resolution by governments the evidence, in my view, does not support the conclusion that it could not have been effectively dealt with under other laws of Canada, as it was in Alberta, or that it exceeded the capacity or authority of a province to deal with it. That was demonstrated not to be the case in Quebec and other provinces and territories including Ontario, except in Ottawa”[6].

For example, section 170 of the Ontario Highway Traffic Act, concerning the prohibition of parking a vehicle on the roadway, could have been applied and did not require the proclamation of a state of emergency to be enforced. We would also point out that section 175 of the Criminal Code, dealing with disturbances of the peace, and section 180 of the Criminal Code, dealing with public nuisances, were available to peace officers to enforce order, even before the Emergency Measures Act was invoked. And that's not counting the numerous municipal by-laws on the use of public places and noise pollution that were in force at the time.

This report also points out that the Commissioner of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) had sent an e-mail to the Chief of Staff of the former Minister of Public Safety, Mr. Marco Mendicino (February 14, 2023), in which she expressed herself very clearly on the subject: “[...] I don't think we've exhausted all the tools available under the existing laws yet”[7]. She went on to list examples of actions that could be taken.

One of the Rouleau report's conclusions was that “It is clear that legal tools and authorities existed; the problem was that these powers, such as the power to arrest, were not being used because doing so was not thought to be an effective way to bring the unlawful protests to a safe and timely end.”[8].

The usual means of intervention and the laws in force were not used or were used incorrectly : disorganized command of the Ottawa Police Service.

The Ottawa police are primarily responsible for this chaos, having failed to take the downtown demonstration seriously. Worse still, the Ottawa Police failed to take proper account of information sent to them by the Ontario Provincial Police about the arrival of the convoy. The first warnings were sent on January 13, 2024, 11 days before the arrival of the trucks[9]. What did the Ottawa police do with this information: close Wellington Street, install controls at the entrances to the City of Ottawa, work with the OPP to develop a response plan? No. The Ottawa Police Service (OPS) command was convinced that the “Freedom Convoy” would leave the nation's capital after just one weekend of protest[10]. This mistaken belief is clearly observed in the Rouleau Commission's final report:

“When preparing for the Freedom Convoy protests, the City of Ottawa relied primarily on information provided by law enforcement agencies, which indicated that the protest would last the weekend and, while potentially disruptive, would be peaceful. However, some information the City received raised the possibility of a longer and more serious protest”[11].

During the Rouleau Commission hearings, a number of internal problems involving the police chief came to light[12]. Testimony suggested that the authority and leadership of OPS Chief Peter Sloly was being challenged within the department. This could explain the absence of an intervention plan and the lack of consistency in the application of existing laws and regulations. Some City of Ottawa police officers even refused to act against protesters, as they were sympathetic to their cause. Concrete examples of this disorganization of OPS command were noted during the Rouleau Commission hearings[13].

We feel it is important to point out that the Chief of the Ottawa Police Service, Mr. Peter Sloly, asked for reinforcements and formulated an official request for 1,800 additional officers, even before the state of emergency was declared[14]. In the absence of an intervention and contingency plan, the Ottawa police did not obtain these resources[15]. Indeed, an extract from the Rouleau Commission report is very revealing in this regard:

On January 30, at noon, the OPS finally requested OPP front-line officers and advised that more requests for assistance would follow. The OPS was so overstretched, however, that it was unable to effectively deploy the OPP officers who began arriving that day. OPP Superintendent Abrams supplied the OPS with 10 officers, but the OPS only deployed two of them. Superintendent Abrams withdrew all 10 officers as a result. He perceived that the OPS’s command dysfunction and poor coordination prevented it from using OPP resources effectively[16].

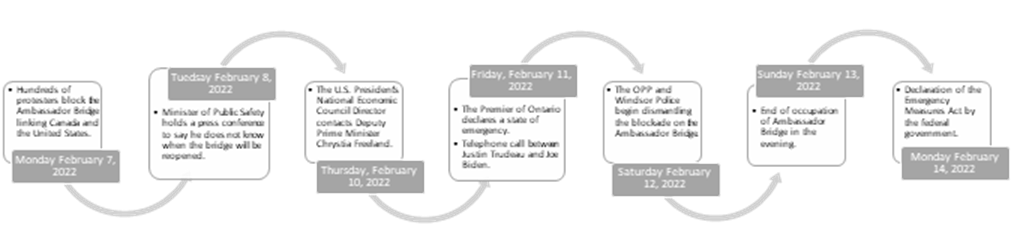

The federal government completely ignored the crisis until a call from U.S. authorities to Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland, in which they “advised” her that the Ambassador Bridge blockade had to be dismantled.

We believe that it was precisely the Detroit-Windsor Bridge incident that led to the Declaration of a State of Emergency, as the Canadian government needed to show the world (especially the U.S.) that it was taking action and taking the situation seriously. The chronology of events, as well as the wording of the Declaration itself, support our hypothesis.

Indeed, the crisis began to unravel in earnest following the U.S. government's appeal. It took the police 2 days to clear the demonstrators from the Ambassador Bridge. The Canadian Prime Minister feared the reaction and perception of the Americans if he did not show himself capable of resolving the problem.

The Emergency Measures Act was applied from February 14, the day the occupation of the Ambassador Bridge ended. It is easy to believe that the Emergency Measures Act was invoked to reassure the United States and restore order in the face of international criticism from all quarters.

Yet this is the same Prime Minister of Canada who told a press conference that it was up to the police to “do their job to resolve the situation”[17] a week after the convoy arrived in Ottawa. He even reportedly told the Premier of Ontario: “You shouldn't need any more legal tools [...] they're crippling the economy, causing millions of dollars in damage every day and hurting people's lives”[18].

So, in front of the Canadian Parliament, despite the proclamation of February 14, 2022, it will take another 5 days before the authorities decide to clear downtown Ottawa. The operation, which was a traditional police intervention, lasted more or less 48 hours, from February 19 to 20, and was far less violent than the repression of other major demonstrations, such as the G20 or the Summit of the Americas. This approach, and the plan that emerged from it, should have been devised at the very outset of events, outlining the various possible scenarios and the measures to be taken for each of them.

The wording of the Declaration of Emergency Measures.

In this context, it is interesting to examine the wording of the Declaration tabled by Justin Trudeau before both Houses. It's very hard not to see the direct link between the proclamation of a state of emergency and the fear of negative American perceptions of Canadian weakness in managing the various occupations.

The first part of the Declaration lists five elements that describe the state of emergency and justify the imposition of the Emergency Measures Act. Here are the main points[19]:

- (a) the continuing blockades and the continuing threats to oppose measures to remove the blockades,

- (b) the adverse effects on the Canadian economy, including trade corridors and international border crossings,

- (c) the adverse effects resulting from the impacts of the blockades on Canada’s relationship with its trading partners, including the United States,

- (d) the breakdown in the distribution chain and availability of essential goods, services and resources caused by the existing blockades;

- (e) the potential for an increase in the level of unrest and violence that would further threaten the safety and security of Canadians.

A state of emergency must first be justified by a genuine threat to Canada's national security. According to Canadian Intelligence, this was not the case[20].

In the second part of the Declaration, the government provides for response measures that do not, for the most part at least, require special emergency legislation. For example, regulating or banning certain types of public gatherings that disturb the peace or threaten essential infrastructure, forcing companies to provide a service to resolve the crisis, imposing fines and prison sentences, or allowing the RCMP to enforce laws outside its jurisdiction (municipal and provincial)[21].

In this regard, the City Manager of the City of Ottawa, Mr. Steve Kanellakos, told the Committee that : “Throughout the ensuing days, [o]ur efforts resulted in approximately 40 heavy trucks and an unknown number of light trucks and vehicles moving out of the residential areas. At around the same time […] the federal government invoked the Emergencies Act. To my knowledge, the city never requested the invocation of the act.”[22]

Indeed, it's understandable that certain actions were possible, even before the Emergency Measures Act was invoked, and were already yielding results.

- 3. COORDINATION AND INFORMATION SHARING

In addition, the government obstructed the Special Joint Committee's examination of the crisis declaration, refusing to produce certain relevant documents to corroborate the testimony explaining the decision to declare a state of emergency.

In particular, the legal opinion rendered just prior to the proclamation of the Emergencies Act, which was invoked by the various ministers who appeared before the Committee and which, presumably, would have recommended the declaration of a state of emergency, was never disclosed in its unabridged and uncensored version. As a client, the government was entitled to waive professional secrecy and could have allowed Committee members access to this advice and other documents covered by professional secrecy.

The Queen's Privy Council also invoked the confidentiality of its deliberations to withhold from the Committee evidence that might have been relevant to the examination of the declaration of a state of emergency.

In the interest of improving the transparency of federal government institutions and fostering public confidence, the Bloc Québécois recommends that the following paragraphs be added to section 62 of the Emergencies Act:

“Evidence

(4.1) The Governor in Council shall disclose to the Parliamentary Review Committee all evidence on which the Governor in Council has reasonable grounds to believe that a national emergency existed.

(4.2) If the evidence disclosed under subsection (4.1) is covered by the confidentiality of the Queen's Privy Council, meetings of the Parliamentary Review Committee to consider it shall be held in camera”.

The OPS had all the information it needed to prepare for the convoy's arrival.

What's more, the OPS's misuse (or even non-use) of the information provided by the OPP is highly surprising. The OPS had been informed at least a week in advance of the convoy's progress and intentions[23]!

This valuable information came from a long-term intelligence operation, as some of the organizers of the 2022 convoy were not new to rodeo. Indeed, Pat King had also been involved in another occupation attempt two years earlier[24]. This was known and public information. Social media allowed the group to get organized. The event was predictable, and even if the scale was uncertain, the OPS had a duty and a responsibility to prepare to the best of its ability. Such was the lack of leadership that the Ontario Provincial Police, who provided Sloly with the information, “even questioned whether the OPS was ‘worthy of assistance’ from other police services”[25].

The subject of this study is as important as it is delicate, since it deals with the conditions under which a government can grant itself extraordinary powers, even though these powers must be exercised in compliance with Canada's Charter of Rights and Freedoms[26]. But it's also a question, in a world full of misinformation and disinformation, of finding the balance between effective information sharing and the protection of national security.

- 4. THE CONFUSION SURROUNDING THE PROTECTION OF THE PARLIAMENTARY PRECINCT.

In closing, the Bloc Québécois deplores the fact that the federal government and the Ottawa police seem to have learned absolutely nothing from all the violent events that have occurred on Parliament Hill since the 1960s! Here are just a few examples of events that should have prompted the federal government to take action[27].

Even the 2014 shootout, in which soldier Nathan Cirillo was murdered, failed to address the issue of the Parliamentary Precinct perimeter and Wellington Street security, which is an aberration. Even today, very little has been done in concrete terms, despite a study of the issue by the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs.

Therefore, the Bloc Québécois recommends: “That this report take into account the conclusions and recommendations of the 19th report of the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs, entitled ‘Protecting the Parliamentary Precinct: Responding to Changing Risks’[28].

The government's inertia in establishing clear roles between the various protection bodies in relation to overflows or events on Parliament Hill is a serious problem that has contributed to the chaos and confusion in the response to the demonstration of January and February 2022.

In 2015, the events of the previous year prompted the creation of the Parliamentary Protective Service (PPS), bringing together the security services of the House of Commons and the Senate, which had previously been completely separate. The PPS answers to the operational command of the RCMP but reports to the Speakers of both Houses and to the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness[29].

This service must therefore ensure security in the Parliamentary Precinct. However, since the renovations to the Centre and East Blocks, the territory has expanded considerably. Especially since rue Wellington, right in front of Parliament, is not part of it! Either the government was so unaware of the crisis as to believe there was no risk of Wellington Street overflowing onto Parliament grounds, or everyone assumed it was the responsibility of the Ottawa Police and looked the other way.

The following is an excerpt from a 1999 report on security in the Parliamentary Precinct:

“A clearly defined Parliamentary Precinct is an essential prerequisite on which all other security measures are contingent. Current boundaries — as defined by the Ottawa River on the north, Wellington Street on the south, the Rideau Canal on the east and the Bank Street extension on the west — create a significant vulnerability. The western boundary no longer has a clear physical definition.95 Members’ offices have been moved outside of traditional Precinct boundaries, into the Confederation Building, the Wellington Building (on the south side of Wellington Street), and the Justice Building (planned for mid-2000). Parliamentary committees meet regularly in both the Wellington and La Promenade Buildings. This situation creates confusion with respect to jurisdiction and has the potential to result in uneven service and response in risk situations” [30]. This can't be serious.

That's why the Bloc Québécois recommends: “that Wellington Street, from the Confederation Bridge to Sussex Street, be included in the Parliamentary Precinct, and that it be under the responsibility of the PPS and the RCMP”.

- 5. CONCLUSION

The occupation of downtown Ottawa by the “Freedom Convoy” for almost a month is a blatant indication of how lightly the government and the Ottawa Police Service take threats. Despite clear indications of the demonstrators' arrival and intentions, nothing was done to protect critical infrastructure, or citizens for that matter.

The Bloc Québécois believes that the proclamation of the Emergencies Act is the heavy artillery of Canadian legislation and should only be invoked in cases of extreme emergency. This guiding principle did not guide the federal government's decision-making during the crisis. The result was a proclamation of the Emergencies Act that was unnecessary, abusive and disrespectful of the opinions of Quebec and the provinces, in addition to covering too large a territory.

The Bloc Québécois wanted to shed light on these issues so that the federal government would become aware of these shortcomings and correct them for the sake of national security and the integrity of our democratic institutions.

[1] Louis Blouin on X : "Voici le rapport de renseignement de la PPO que le chef de police Sloly avait en main avant l'arrivée des camionneurs. Il a quand même laissé les camions s'installer au centre-ville. #polcan #CEDU https://t.co/M5KSWG9Ux4" / X

[2] Criminal Code, Section 63.

[3] Draft Committee Report DEDC, par. 58

[4] Draft Committee Report DEDC, par. 56

[5] Canadian Frontline Nurses v. Canada (Attorney General), 2024 FC 42, par. 248 (EA-challenge-fed-court-reasons-FINAL.pdf)

[6] Canadian Frontline Nurses v. Canada (Attorney General), 2024 FC 42, par. 254 (EA-challenge-fed-court-reasons-FINAL.pdf)

[7] Draft Committee Report DEDC, p.102

[8] Report of the Public Inquiry into the 2022 Public Order Emergency. Vol. 3 : Analysis (part 2) and recommendations. p.206.

[9] Report of the Public Inquiry into the 2022 Public Order Emergency. Vol. 2 : Analysis. page 141.

[10] « Convoi de la liberté » : la PPO avait aussi averti du risque d’occupation | Commission d'enquête sur l'état d'urgence | Radio-Canada

[11] Report of the Public Inquiry into the 2022 Public Order Emergency. Vol. 1 : Overview. p.47

[12] « Convoi de la liberté » : la PPO avait aussi averti du risque d’occupation | Commission d'enquête sur l'état d'urgence | Radio-Canada

[13] Report of the Public Inquiry into the 2022 Public Order Emergency. Vol. 1 : Overview. p.45

[15] « Convoi de la liberté » : la PPO avait aussi averti du risque d’occupation | Commission d'enquête sur l'état d'urgence | Radio-Canada

[16] Report of the Public Inquiry into the 2022 Public Order Emergency. Vol. 2 : Analysis. p.192

[18] Blocage du pont Ambassador : Trudeau était prêt à accepter de l’aide des Américains | Commission d'enquête sur l'état d'urgence | Radio-Canada

[20] Draft Committee Report, par 144 and 158

[21] Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act (art. 20(1) et (2)).

[22] Evidence - DEDC (44-1) - No. 16 - Parliament of Canada, Kanellakos (1845).

[23] Report of the Public Inquiry into the 2022 Public Order Emergency. Vol. 1 : Overview. pp.43-45

[26] Evidence - DEDC (44-1) - No. 3 - Parliament of Canada, Philippe Hallée (1840).