DEDC Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Review of the Exercise of Powers and the Performance of Duties and Functions Pursuant to the Declaration of Emergency that was in effect from February 14, 2022, to February 23, 2022

Chapter 1: Introduction

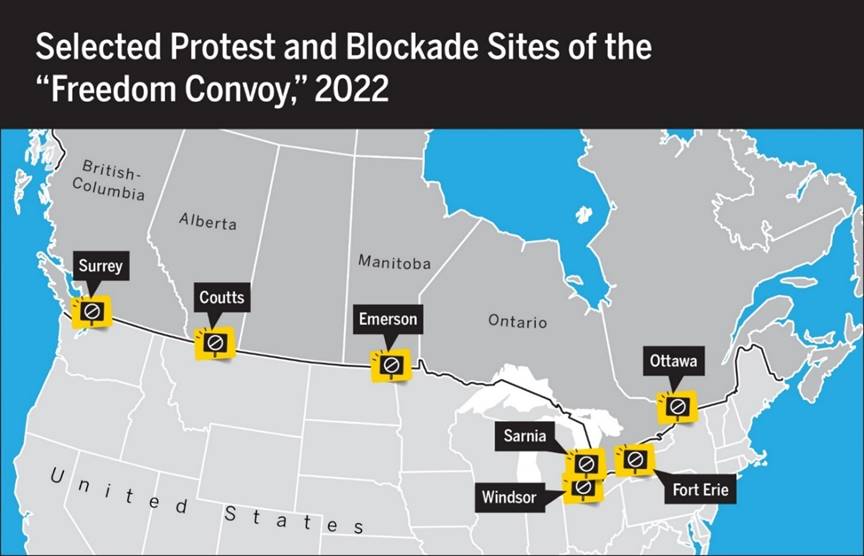

On 28 January 2022, the first protest associated with the “Freedom Convoy” began in Ottawa, Ontario. Over the subsequent days and weeks, several additional protests and blockades would take place across Canada, including in Coutts, Alberta; Surrey, British Columbia; Emerson, Manitoba; Fort Erie, Ontario; Sarnia, Ontario; and Windsor, Ontario. Several smaller protests would also emerge in other locations across Canada. Figure 1 shows the locations of some of these protests and blockades.

Figure 1—Selected Locations of “Freedom Convoy” Protests and Blockades, January to February 2022

Source: Figure created by the Special Joint Committee on the Declaration of Emergency based on various media reports.

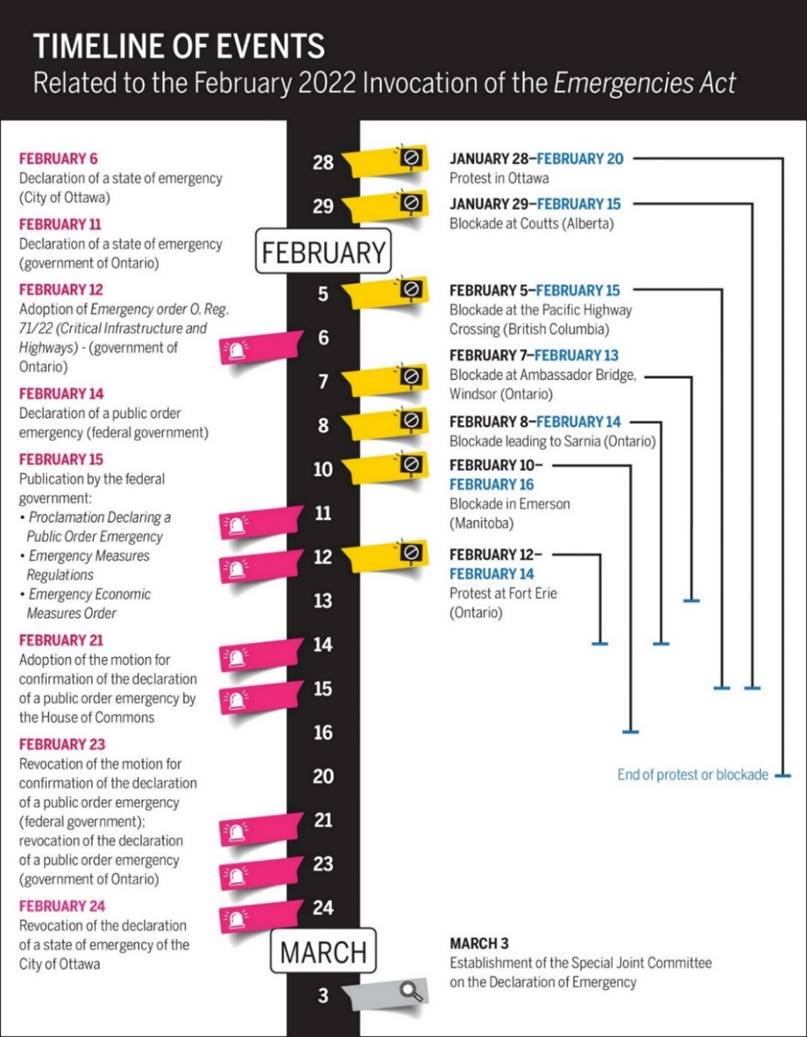

In response to these events, several levels of government declared states of emergency. Figure 2 shows the timeline of these states of emergency in relation to the various protests and blockades that were taking place at the time.

Figure 2—Timeline of Events Related to the 2022 Invocation of the Emergencies Act

Source: Figure prepared by the Special Joint Committee on the Declaration of Emergency based on data obtained from various government and media sources.

On 6 February 2022, the City of Ottawa declared a state of emergency.[1] On 11 February, the Government of Ontario declared its own state of emergency “as a result of interference with transportation routes and critical infrastructure in locations across the province.”[2] On 12 February, the Government of Ontario made an emergency order under the Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act, which prohibited persons from blocking critical infrastructure, among other measures.[3]

On 14 February 2022, pursuant to section 17 of the federal Emergencies Act (the Act), the Governor in Council declared the existence of a public order emergency.[4] The Proclamation Declaring a Public Order Emergency stated that the emergency consisted of:

(a) the continuing blockades by both persons and motor vehicles that is occurring at various locations throughout Canada and the continuing threats to oppose measures to remove the blockades, including by force, which blockades are being carried on in conjunction with activities that are directed toward or in support of the threat or use of acts of serious violence against persons or property, including critical infrastructure, for the purpose of achieving a political or ideological objective within Canada,

(b) the adverse effects on the Canadian economy—recovering from the impact of the pandemic known as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19)—and threats to its economic security resulting from the impacts of blockades of critical infrastructure, including trade corridors and international border crossings,

(c) the adverse effects resulting from the impacts of the blockades on Canada’s relationship with its trading partners, including the United States, that are detrimental to the interests of Canada,

(d) the breakdown in the distribution chain and availability of essential goods, services and resources caused by the existing blockades and the risk that this breakdown will continue as blockades continue and increase in number, and

(e) the potential for an increase in the level of unrest and violence that would further threaten the safety and security of Canadians.[5]

On 15 February 2022, the Governor in Council made the Emergency Measures Regulations (Regulations) and the Emergency Economic Measures Order (Order).[6] The Regulations put in place measures to regulate or prohibit public assembly and required that individuals comply with a request for essential goods or services made by certain officials “for the removal, towing and storage of any vehicle, equipment, structure or other object that is part of a blockade.”[7]

Among other measures, the Order provided a regime for certain financial institutions to cease certain dealings with individuals or entities “engaged, directly or indirectly, in an activity prohibited by sections 2 to 5 of the Regulations,” such as participating in a public assembly that may reasonably be expected to lead to a breach of the peace.[8]

Within a few days of the Regulations and the Order, all the protests and blockades concluded. Beginning on 18 February 2022, a police operation took place in Ottawa that successfully brought an end to the protest that had effectively turned into an occupation of downtown Ottawa. Protests and blockades in other locations across Canada also came to an end.

Section 62 of the Emergencies Act provides that a parliamentary review committee must review the exercise of powers and the performance of duties and functions pursuant to a declaration of emergency. As such, the Special Joint Committee on the Declaration of Emergency (the Committee) began its review on 24 March 2022.

During its review, the Committee heard from 79 witnesses over 16 meetings. Witnesses included federal ministers, departmental officials and representatives from policing services, municipal government, the financial sector and related industries. The Committee also received four written briefs and hundreds of pages of written documentation from several federal departments and agencies.[9] The Committee wishes to sincerely thank all those who participated in this review for their valuable contribution to an important parliamentary evaluation of the first ever use of the Emergencies Act.

Section 63 of the Emergencies Act requires that an inquiry related to the emergency be established within 60 days after the expiration or revocation of a declaration of emergency. As such, on 25 April 2022, an order in council was published creating the Public Order Emergency Commission (the Commission).[10]

This report summarizes the evidence considered by the Committee, particularly the testimony of the witnesses who appeared before the Committee, organized into the following chapters: Parliamentary Supervision, Impact of the “Freedom Convoy,” Political Response to the “Freedom Convoy,” Police Response to the “Freedom Convoy,” National Security and the “Freedom Convoy,” Invocation of the Emergencies Act, Special Temporary Measures, Charter Compliance, and Access to Information and Documents. The report also includes recommendations to the federal government.

In preparing this report, the Committee has considered the evidence of the Commission as it relates to the exercise of powers and the performance of duties and functions pursuant to the declaration of emergency. The Commission released its final report on 17 February 2023.[11] On 6 March 2024, the federal government released its response to the Commission’s report.[12]

Chapter 2: Parliamentary Supervision

The Emergencies Act provides a regime for the parliamentary supervision of a declaration of emergency, including:

- the consideration of a motion for confirmation of a declaration of emergency by the Senate and House of Commons;

- parliamentary involvement in the revocation, continuation or amendment of a declaration of emergency;

- parliamentary involvement in the revocation or amendment of any order or regulation made pursuant to the Emergencies Act;

- the parliamentary review committee; and

- an inquiry “to be held into the circumstances that led to the declaration being issued and the measures taken for dealing with the emergency.”[13]

Pursuant to subsection 58(1) of the Emergencies Act, the motion for confirmation of a declaration of emergency was tabled in the House of Commons on 16 February.[14] The House of Commons debated the motion from 17 to 21 February and agreed to it on a recorded division on 21 February.[15]

In the Senate, the motion for confirmation of a declaration of emergency was moved on 21 February.[16] The Senate debated the motion from 22 to 23 February.[17]

The declaration of emergency was revoked on 23 February 2022, when the Governor in Council made the Proclamation Revoking the Declaration of a Public Order Emergency.[18] As a result, in the Senate, the motion for confirmation was withdrawn and did not come to a vote.

Subsection 62(1) of the Emergencies Act provides that a joint committee composed of both senators and members of Parliament shall review “[t]he exercise of powers and the performance of duties and functions pursuant to a declaration of emergency.”

On 2 March 2022, the House of Commons adopted a motion to establish a special joint committee “to review the exercise of powers and the performance of duties and functions pursuant to the declaration of emergency that was in effect from Monday, February 14, 2022, to Wednesday, February 23, 2022.”[19]

On 3 March 2022, the Senate adopted a similar motion to establish a special joint committee, providing it with a mandate that has identical language to the motion adopted by the House of Commons.[20]

On 5 April 2022, the Committee adopted a motion that, among other things:

[T]he committee begin its study, pursuant to s. 62(1) of the Emergencies Act, of the options that the Government of Canada utilized during the invocation of the Emergencies Act and enumerated in the Proclamation Declaring a Public Order Emergency.

That in this study of each option and for the committee’s final report, the committee consider the necessity, implementation, and impact of that option.[21]

The Emergencies Act requires the parliamentary review committee to report the results of its review to both houses of Parliament at least once every 60 days while a declaration of emergency is in effect and empowers the Committee to revoke or amend any order or regulation.[22] As such, as the Emergencies Act was drafted, the parliamentary review committee was intended to provide ongoing oversight while a declaration of emergency was in effect, rather than post facto review like the Commission.

In this case, due to the short duration of the declaration of emergency, the Committee was established after the declaration of emergency had already been revoked. As such, there was no ability for the Committee to report back to both houses on an ongoing basis during the declaration of emergency, and the Committee did not have the opportunity to revoke or amend any orders or regulations.

Given that the Committee and the Commission undertook their work simultaneously, the Committee invited three witnesses to appear to explain the scope of the Committee’s mandate.

Philippe Hallée, Senate Law Clerk and Parliamentary Counsel, and Philippe Dufresne, House of Commons Law Clerk and Parliamentary Counsel, explained that, in accordance with the Emergencies Act and the motions adopted by both houses, the Committee had the authority to review the exercise of powers and the performance of duties and functions pursuant to the declaration of a public order emergency, while the question of whether any other topics were within the scope of its mandate was for the Committee to decide.[23]

As the minister who sponsored the Emergencies Act in Parliament when it was enacted in 1988, the Honourable Perrin Beatty provided the Committee with insight about the intended role of the Committee:

We anticipated that the primary role of the committee was going to be to provide continuing parliamentary oversight, throughout the time of the crisis, of how the government was using its authority. What we certainly did not preclude was the ability of the committee to look at whether or not the authority that the government had given itself was appropriate.[24]

The Honourable Perrin Beatty also argued that the Committee should study the circumstances that caused the declaration of emergency and seek information that sheds light on the rationale for the invocation of the Emergencies Act. Finally, he said that it would be appropriate for the Committee to examine whether the threshold for the invocation of the Emergencies Act was met.[25]

In his brief to the Committee, Ryan Alford, Professor at Lakehead University, noted that the Committee could address whether there was an emergency as defined by the Emergencies Act. He explained that, as “an organ of parliamentary oversight and responsible government,” the Committee should hold the government accountable for its conduct both during the declaration of emergency and at the Commission.[26]

Some witnesses also addressed the overlapping mandates of the Committee and the Commission.[27] The Honourable Perrin Beatty indicated that he was not offended by the overlap between the Committee and Commission, and he thought that it would be “healthy in a democracy” if the two bodies reached different conclusions.[28]

However, in a brief submitted to the Committee, Nomi Claire Lazar, Professor at the University of Ottawa, explained that there was confusion among experts caused by the simultaneous reviews of the Committee and the Commission.[29] She elaborated that:

[O]verlapping investigations result in public confusion, exhaustion, expense, and the risk of divergent conclusions and recommendations. The current process risks generating a public perception of politicization of the fact-finding process. And these factors together may undermine public trust in the mechanisms of accountability, in turn undermining their effectiveness.[30]

She invited the Committee to consider its role as a forum for robust public debate beginning after fact finding is completed “by a single body whose neutrality the public widely accepts.”[31]

The Commission’s final report recommended that the Emergencies Act be amended to clarify the mandate and timing of a parliamentary review committee.[32] In its response to the Commission’s recommendations, the federal government agreed that it would be beneficial for the parliamentary review committee to be struck “as soon as possible to allow it to exercise its oversight function, and that the Committee’s review be conducted expeditiously.”[33] However, the federal government did not necessarily commit to amending the Emergencies Act to bring about those changes, but rather proposed further consultations on a range of potential amendments to this Act.

Given the Committee’s experience and evidence received from witnesses with respect to its timing and the timing of the Commission, the Committee agrees that, in the future, the parliamentary review committee’s work should begin sooner after an emergency is declared. As such, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 1

That the federal government amend the Emergencies Act to ensure that the parliamentary review committee:

- is appointed within 48 hours after the proclamation of the emergency;

- sit only over the course of the emergency in an oversight capacity; and

- not sit simultaneously with the inquiry provided for in section 63 of the Emergencies Act.

Recommendation 2

That the federal government amend the Emergencies Act to require that the motion considered in each house of Parliament to confirm a declaration of emergency also make provision for the designation or establishment of the parliamentary review committee, so as to ensure that the committee becomes active at the earliest possible opportunity.

The Committee recognizes that other aspects of its review might have to take place differently in the future. For instance, although the Committee found the legal assistance provided by the Senate and House of Commons law clerks to be very helpful, the Committee can foresee future scenarios in which it might need to engage external legal counsel to properly conduct its work.

In any case, with respect to how the Committee ought to operate in the future, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 3

That the Senate and House of Commons administrations provide any future parliamentary review committee with an overriding priority to access the use of parliamentary resources available for committee meetings during a period of national emergency.

Finally, in relation to broader public accountability and the inquiry process, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 4

That the federal government collaborate with Parliament to ensure that the Emergencies Act is amended to include an automatic review of the Act itself by way of a joint parliamentary committee, either within the 12 months following the production of the final report on the mandated inquiry when the Act has been invoked, or every 10 years when the Act has not been invoked.

Chapter 3: Impact of the “Freedom Convoy”

Impact on Residents and Communities

Many witnesses said that the “Freedom Convoy” protests and blockades had a significant effect on residents’ well-being, the livability of the neighbourhood and their safety.[34] Beyond the constant barrage of noise and diesel fumes, these residents experienced stress, psychological distress, sleep deprivation, hearing loss, and even suicidal thoughts, while dealing with protesters’ aggressive and intimidating behaviour. The constant honking was particularly traumatic for residents of downtown Ottawa.[35] Mayor of Ottawa Jim Watson said that the combined presence of 18 wheelers and vehicles in the downtown core felt like “an overpowering and threatening armada” for residents.[36] The Mayor of Coutts, Jim Willett, said that many elderly residents in his community were afraid to travel through the protest area because they felt intimidated by the protesters.[37]

Ottawa city councillor Mathieu Fleury said that some residents were still traumatized by the experience months later.[38] Some witnesses highlighted that the emergency and distress call volume increased significantly in relation to events associated with the “Freedom Convoy.”[39] For example, the City of Ottawa had over 18,000 3-1-1 calls, which is significantly higher than the normal volume.[40]

A number of witnesses also said that those involved in restoring order, including police officers, bylaw officers and snowplow operators, suffered mental anguish and exhaustion.[41] Stephen Laskowski, President of the Canadian Trucking Alliance, spoke about the consequences for truckers stuck in the blockades, including the impact on their livelihoods.[42]

Furthermore, some witnesses told the Committee that many residents and workers experienced travel disruptions.[43] Some services had to be relocated or interrupted.[44] For instance, in Ottawa, staff at the Montfort Hospital had to stay in nearby hotels because of major traffic delays, leading to a steep decline in activity in the emergency room.[45] As well, 13 families had to delay or reschedule cancer treatments at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario.[46] Jim Willett added that, in Coutts, school buses and courier services could not cross the protest area.[47]

Lastly, in terms of lessons learned from the experience, witnesses from the City of Ottawa explained that proactively closing streets to traffic could have prevented the blockades from happening and trucks from being set up downtown.[48] Furthermore, mistakes – such as allowing trucks to use non-truck routes, allowing protesters to bring recreational equipment to the protest area, and failing to inform residents and businesses about the authorities’ plans – could have been avoided.[49]

Economic Impact

Various witnesses stated that many businesses were affected by the “Freedom Convoy,” whether financially or by being forced to temporarily or fully suspend their activities, particularly because they were unable to receive deliveries.[50] Mathieu Fleury said that it was “chaos”[51] for businesses and institutions in the area. Specifically, the Rideau Centre was closed for 24 consecutive days, representing a loss of revenue of $2 million per day for those businesses.[52]

Mathieu Fleury also said that small and independent businesses were particularly hard hit. Some restaurant owners faced stark choices: they could either serve protesters in violation of public health regulations or close entirely.[53] Jim Watson added that the tourism industry was also affected.[54]

Various witnesses told the Committee about the significant economic impacts associated with the illegal border blockades.[55] For example, the City of Windsor spent $5.7 million to end the blockade, and it has been calling for the governments of Ontario and Canada to reimburse the municipality.[56]

On the other hand, in its brief to the Committee, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association remarked:

There were concerns about the economic impacts of the border blockades that may, over a long period, have posed a serious threat to health and safety. However, when the emergency was declared, there was no compelling evidence that Canadians were at risk of going without necessities. The economic harms did not amount to circumstances that seriously endangered Canadians’ lives, health or safety.[57]

Many witnesses highlighted the economic impact at the national level of the blockade of the Ambassador Bridge in Windsor, particularly for the automotive industry.[58] The top concern for many witnesses was supply chain disruptions with American trade partners.[59] Some witnesses said that diverting goods to other border crossings was not an adequate solution, because none of the other crossings have the same capacity as the Ambassador Bridge.[60]

In addition, some witnesses were concerned about Canada’s reputation in international trade and how border infrastructure blockades could affect foreign investment in Canada.[61] In February 2024, the Honourable Dominic LeBlanc, Minister of Public Safety, Democratic Institutions and Intergovernmental Affairs, reiterated that the blockade of the Ambassador Bridge affected $390 million in trade between Canada and the United States every day, given that 30% of all trade by road between the two countries uses that crossing.[62]

The Committee acknowledges the impact of the “Freedom Convoy” on many individuals and entities in a variety of sectors. Therefore, the Committee believes that, following an emergency as defined in the Emergencies Act, it could prove useful to hold consultations with people representing the affected regions to determine the extent of the damage and the mitigation measures that could be taken to prevent similar future occurrences.

Chapter 4: Political Response to the “Freedom Convoy”

As a multijurisdictional event that took place in multiple municipalities within several provinces, all three levels of governments were implicated to some extent in the response to the “Freedom Convoy.” Other than the federal government, several other governments declared states of emergency in response to the events of January and February 2022. These included the Government of Ontario, the City of Ottawa and the City of Windsor.

Pursuant to the Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act, the Government of Ontario declared a state of emergency on 11 February 2022. The state of emergency allowed the provincial government to enact Ontario Regulation 71/22: Critical Infrastructure and Highways, which prohibited the blocking of critical infrastructure, among other measures.[63] According to the province, the emergency order was necessary because existing regulation-making powers were not successful in alleviating the harm caused by the blockades in Ottawa and at the Ambassador Bridge.[64]

In relation to the federal government’s decision to invoke the Emergencies Act, section 25 of the Act requires that the “lieutenant governor in council of each province in which the effects of the emergency occur shall be consulted with respect to the proposed action.” That section also provides that if a province cannot be adequately consulted before the issue or amendment of a declaration of public order emergency, the consultation may take place after the fact.

On 16 February 2022, the Honourable Marco Mendicino, former Minister of Public Safety, tabled his Report to the Houses of Parliament: Emergencies Act Consultations in the House of Commons.[65] The same report was tabled in the Senate by the Honourable Senator Marc Gold, Government Representative in the Senate, on 21 February.[66]

The report detailed the consultations that had taken place since late January 2022 between the federal government and provincial, municipal and international partners. It described a First Ministers’ meeting that was held on 14 February 2022, to consult premiers on whether to declare a public order emergency, and included an annexed letter from the prime minister to the premiers indicating that their views had been taken into account in determining what the special temporary measures would consist of in response to the “Freedom Convoy.”[67]

Although the Report to the Houses of Parliament: Emergencies Act Consultations mentions that the federal government consulted Indigenous leaders regarding the blockades, the Committee agrees that there is a duty to consult before the invocation of the Emergencies Act. As such, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 5

That the federal government amend the Emergencies Act to provide that it be required to undertake and set the parameters for consultations with Indigenous peoples prior to the invocation of the Emergencies Act, with due regard to the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, including justice, democracy, respect for human rights, non-discrimination and good faith.

The Committee agrees that the Emergencies Act should be amended to take greater consideration of provincial governments and require the federal government to provide more information on the national nature of the emergency. Evidence received by the Committee and the Commission supports this position. For instance, Leah West testified at the Committee:

At the same time, I would say that we also need to amend what consultation is from the federal government to the provinces, and make something of required meaningful consultation on that end as well. We shouldn’t be looking at one without the other.[68]

At the Commission, the provincial governments of Saskatchewan and Alberta decried the fact that the provinces were not adequately consulted by the federal government before the invocation of the Emergencies Act.[69]

The Commission’s report states that the 14 February First Ministers’ Meeting “was the only time the premiers were asked for their views on the invocation of the Emergencies Act.”[70] The report goes on to explain:

I certainly agree that the premiers had little time to prepare and that the notice they received was not explicit regarding the topic to be discussed at the First Ministers’ Meeting. That said, in the context of the events, the topic of discussion probably did not come as a surprise to many of the participants.

The Federal Government indicated to the Commission that one of the reasons it did not inform the provinces of the purpose of the meeting was the concern that news could leak, and the potential for the declaration of an emergency could anger protesters and increase the risk of violence. I accept this point as valid, though I would characterize it as one taken out of an abundance of caution.[71]

During his testimony before the Commission, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau also described how it was decided at the Cabinet meeting of 13 February that provincial premiers would be consulted the next day and a telephone meeting took place with the Liberal caucus before that meeting was held.[72] The prime minister also explained that the First Ministers’ Meeting took place by conference call, and it lasted approximately one hour.[73] During that meeting, the premier of Saskatchewan remained against the invocation of the Emergencies Act, and the premier of Alberta said that it did not need to be used in Alberta.[74]

The Report to the Houses of Parliament: Emergencies Act Consultations further specifies that the provinces of Quebec, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island commented that the Emergencies Act was not necessary in their respective provinces.[75]

Witnesses at the Committee also discussed the national nature of public order emergencies under the Emergencies Act. Perrin Beatty testified that

[i]t has to meet the standards of the national emergency. The consequences have to be so severe that the welfare of the country as a whole is affected. However, that does not mean that an emergency has to take place in all regions of the country.

[…]

We wanted to have legislation that would allow the government to say, “[t]here’s a grave crisis here. It meets the definition of a national emergency, but we aren’t going to suspend everybody’s rights; we’re going to target it.[76]

Finally, Ryan Teschner, Executive Director and Chief of Staff for the Toronto Police Service Board, told the Commission that

[If] the government doesn’t put on the table what invoking means, what are the specific regulations that they may put in place as a result of invoking the Act? What are the impacts of those regulations on some of the actors who are going to be impacted? I don’t know how you can have meaningful consultation in the absence of exploring those dimensions.[77]

Many witnesses commented on the political response to the “Freedom Convoy” at the federal level of government, including the consultations and meetings that took place before and after the invocation of the Emergencies Act.[78] More specifically, former Minister Mendicino and the Honourable Bill Blair, former Minister of Emergency Preparedness, discussed the role played by the federal government in working with police and participating in consultations with other levels of government. Former Minister Mendicino told the Committee that the federal government “remained engaged with law enforcement throughout to ensure that they had the support and the resources they needed.”[79] He also discussed the ongoing consultations that took place with the provinces and territories, which took place through the implementation of the special temporary measures enacted during the declaration of emergency.[80] For his part, former Minister Blair testified about his communications with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and other police leadership in relation to the blockades in Coutts, as well as possible options to secure tow trucks.[81]

Some mayors of affected municipalities testified that they felt supported by the federal government overall. Jim Watson testified that he participated in several meetings with federal representatives and that he spoke directly with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau as early as 3 January.[82] Drew Dilkens, Mayor of the City of Windsor, explained:

I felt that as Mayor of Windsor I had the ear of both federal and provincial government representatives at the highest levels, including [former] Minister Mendicino, [former] Minister Blair, Ontario Solicitor General Jones, Premier Ford and Prime Minister Trudeau. My staff was in contact with and coordinated with political staff across federal and provincial ministers’ offices and the security establishment.[83]

In a similar vein, Steve Kanellakos, City Manager of the City of Ottawa, said that Deputy Minister Rob Stewart of Public Safety Canada proactively reached out to him after the first weekend of the protests to talk, and he became a key contact between the City of Ottawa and the federal government.[84]

However, some witnesses from impacted municipalities highlighted areas for improvement regarding their relationships with the federal government in responding to emergencies such as the one experienced in January and February 2022. Steve Kanellakos testified about the need for a memorandum of understanding between the federal government and the City of Ottawa for dealing with large-scale emergencies such as the one experienced during the “Freedom Convoy.”[85]

Drew Dilkens also commented that the federal and provincial governments should indemnify the City of Windsor for the significant unforeseen costs that were incurred as a result of the blockade of the Ambassador Bridge in Windsor.[86] Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 6

That the municipalities that bear costs reasonably incurred as a result of an emergency (such as, jersey barriers) be indemnified in the event of such expenses; and that a tripartite roundtable composed of federal, provincial and municipal appointees be convened to discuss these costs in the aftermath of an emergency.

At the provincial level, some witnesses were critical of the level of involvement of the Government of Ontario and Premier Doug Ford in meetings related to the response to the “Freedom Convoy” and the lack of responsibility taken by the province for certain elements surrounding the “Freedom Convoy.”

For example, Jim Watson shared with the Committee that the Government of Ontario declined to take part in the tripartite committee dialogue involving the City of Ottawa, the federal government and the Government of Ontario.[87] He also highlighted that Premier Ford did not visit Ottawa during the protests.[88] The brief submitted by the Canadian Civil Liberties Association also took the position that the Government of Ontario “did not meaningfully respond to the protests until around February 9.”[89] Jody Thomas, National Security and Intelligence Advisor, Privy Council Office, attempted to explain the absence of the Government of Ontario in testifying that:

Ontario determined that this was a protest in the federal capital because of the federal mandate, and was therefore a federal problem. It was a much more complex issue than that. They did not come to the table, to the extent that we would have appreciated, because of that.[90]

Drew Dilkens explained that greater collaboration and support from both the federal and provincial levels were needed to improve safety and security at the Canadian borders.[91]

Both Ontario Premier Doug Ford and Deputy Premier Sylvia Jones, who was Solicitor General of Ontario during the “Freedom Convoy,” declined invitations to appear as witnesses before both the Committee and the Commission. The Commission challenged the refusal to testify in the Federal Court, and the Federal Court ruled that the premier and deputy premier could not be compelled to testify before the Commission due to the immunity provided to them as part of their parliamentary privilege.[92]

The Committee recommends therefore:

Recommendation 7

That the federal government amend the Emergencies Act to provide a clear and delineated role for the provinces in the event of future disruptions, and that, as part of this exercise: (a) there should be a review of policing roles, including jurisdictional responsibilities; (b) the three levels of government should enter into an agreement that clearly delineates those roles and responsibilities in the event of an emergency in the National Capital Region and at border crossings; and (c) other crucial areas and infrastructure should also be considered within this review.

Chapter 5: Police Response to the “Freedom Convoy”

Police from all levels of government were involved in the response to the “Freedom Convoy” protests and blockades before and during the declaration of emergency. Specifically, the RCMP, the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP), and the Ottawa Police Service (OPS) were the main policing agencies implicated at the time.[93]

Other provincial and municipal policing agencies involved in policing the events that led to the declaration of emergency included the Toronto Police Services, the Windsor Police Services, York Regional Police, Sûreté du Quebec, Gatineau Police and Peel Regional Police.[94] Smaller municipalities, such as Coutts, Alberta, are policed by the RCMP through Police Services Agreements.[95]

The federal government has a role to play in the direction of the RCMP. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act provides that the Commissioner of the RCMP holds office “under the direction of the Minister” of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness.[96] However, the Commissioner “has the control and management of the Force and all matters connected with the Force.”[97]

The Police Services Act provides that the Solicitor General of Ontario may arrange to provide police services in an emergency.[98] Indeed, the OPP was involved early on in supporting the policing response to the “Freedom Convoy,”

[In] providing intelligence reports to law enforcement partners, dialoguing with convoy organizers, and working with municipal police services to provide resources.[99]

The OPS experienced changing leadership during the protests in Ottawa. Peter Sloly served as Chief of the OPS from 28 October 2019 to 15 February 2022, when he resigned. Subsequently, Steve Bell was appointed Interim Chief of the OPS.

To ensure the security of the Parliamentary Precinct, several organizations were involved in monitoring or responding to the events that took place on Parliament Hill, including the OPS, the Parliamentary Protective Service (PPS), the Senate’s Corporate Security Directorate, and the Office of the Sergeant-at-Arms and Corporate Security of the House of Commons.

The PPS was created following a memorandum of understanding (MOU) signed in June 2015 between the speakers of the Senate and House of Commons, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness and the Commissioner of the RCMP.[100] That MOU provided that the PPS “is established to provide integrated physical security throughout the Parliamentary Precinct and the grounds of Parliament Hill.”[101] It also set out the role of the Director of the PPS:

The Director will be responsible for planning, directing, managing and controlling operational parliamentary security […] taking into account the objectives, priorities and goals as set by the Speaker of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Commons.[102]

In another MOU between the RCMP and the House of Commons concerning the sharing of information for the purpose of enhancing the safety and security of the House, the responsibilities of each organization were further specified. This MOU provided that the House, through the Sergeant-at-Arms, “has the right and mandate to ensure the safety and security of the House” and “complete and sole authority to regulate and administer its precinct.”[103] An equivalent MOU between the RCMP and the Senate, if it exists, was not shared with the Committee.

Challenges Faced by Police

Many witnesses commented that the protests and blockades stemming from the “Freedom Convoy” were unprecedented.[104]

Several witnesses explained that the size of the demonstrations, especially in Ottawa, presented unique challenges for police, including a lack of resources to manage the protests safely.[105] Brenda Lucki, Commissioner of the RCMP, discussed how the size and entrenched nature of the protest in Ottawa made it difficult to ensure public safety:

This was completely a different type of protest, where people were not leaving. Our police liaison teams were trying to motivate people to leave, because when we’re dealing with a mass protest, it’s all about reducing that footprint so that we can be as safe as we can with enforcement action. When the weekend was full of protesters, it was not the time to do any type of enforcement, because it was too dangerous for the public and the police.[106]

According to the OPS, the size of the protest in Ottawa also made it difficult to staff the protest with an adequate number of police officers, with 2,200 officers required in the end to bring the protest to an end.[107] Referring to his 7 February formal request for 1,800 additional officers, Peter Sloly, retired Chief of Police of the OPS, explained:

The primary requests that I made on a continual basis were for resources, particularly more police officers and police-trained personnel, and secondarily, access to tow trucks. It was predictable access to a large number of officers—1,800—and access to predictable, sustainable levels of heavy tow trucks.[108]

Some witnesses suggested that a lack of leadership among the protesters made it more difficult to negotiate a conclusion to the protests or the removal of trucks from residential areas of Ottawa.[109] In this vein, Peter Sloly explained:

In many occasions, there is a singular organizing body or a significant influencer within a protest group. This was not the case. There were significant efforts by multiple jurisdictions and multiple agencies at all three levels of policing to seek negotiated agreements, reasonable understandings and commitments, but there was never a unified “other” with which any police agency could come to any substantive understanding as to whether what was agreed to would actually happen on the day of.[110]

However, there was some success in relocating some of the heavy trucks used as part of the protest in Ottawa. According to Steve Kanellakos, the municipality was advised that the protesters wished to meet with a senior city official, and those talks culminated in the relocation of approximately 40 heavy trucks.[111]

Many witnesses noted that the use of vehicles, including heavy trucks, to protest presented difficulties in the policing response to the protests and blockades, both within and outside of Ottawa.[112] Jim Watson identified the inability to move the trucks as the biggest challenge faced in Ottawa.[113]

Some witnesses explained that it was not possible to identify available tow truck drivers to assist in any efforts to relocate or remove the heavy trucks.[114] Brenda Lucki explained some of the reasons why tow truck companies refused to cooperate:

There were tow truck companies that were receiving funds through the protest not to assist us. Some of the individuals in the companies were very worried about their safety and their livelihood, and they were experiencing a lot of harassment.[115]

Other aspects of the heavy trucks proved also to be a source of concern for some witnesses. Larry Brookson, Acting Director of the PPS, expressed apprehension about the content of the trucks, which was unknown at the time, stating:

The reality for me is I didn’t know what was in those vehicles, and I had no means to verify what was in those vehicles, so that was a constant security concern for me throughout the days of the occupation.[116]

The Committee heard further testimony about the impact of the declining public trust and confidence in police leadership, especially in Ottawa.[117] In justifying his decision to resign as chief of the OPS during the protests in Ottawa, Peter Sloly explained that any decline in public trust creates a public safety risk, and in Ottawa, this contributed to a slowing down of resources:

Declining public trust creates a public safety risk in any policing organization, any policing environment. The focus of that was increasingly on the Ottawa Police Service for a national security crisis, and increasingly on the officer who held that position, chief of police, which was me. My interpretation—others will have their own opinions—was that a declining level of trust in my officers and in my office was potentially slowing down resources and supports necessary for our officers to be able to safely and successfully end this. I took myself out of the equation because I wasn’t going to take 1,400 people out of the equation.[118]

In response to criticism among members of the public that the OPS did not do enough during the demonstrations to enforce existing statutory authorities, Peter Sloly commented that bylaws, provincial statutes and criminal offences were enforced “when [police] could do so safely and without further escalating an already highly volatile situation.”[119]

However, Steve Bell, Interim Chief of the OPS, expressed his hope that trust could be rebuilt among residents of the City of Ottawa. He noted that the OPS was in the process of “working to rebuild public trust with our community members […] that period of time [during the protests] left them with a lack of a feeling of safety and security.”[120]

Finally, several witnesses discussed challenges stemming from a lack of accurate intelligence about the nature and intent of the “Freedom Convoy.”[121] Steve Kanellakos explained to the Committee how initially, based on the intelligence that was received, police and city officials expected the protests to be similar to others previously experienced in the nation’s capital:

I think that the assumptions that were made leading into the first weekend were that it was within the usual paradigm of the hundreds of protests we have every year in the city of Ottawa and that the advanced planning that would have been required—to some of the other questions we’ve been asked—to effectively deal with that weekend were not in place, so we got behind as a city and as a police service. We got behind the event and could not get ahead of it then because the resources were not adequate to meet it.

The biggest lesson, in my mind—and there’s been a lot of discussion at the public inquiry—is that the intelligence translating into strategy was a big gap.[122]

Kent Roach, Professor at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Law, suggested that the police do not have necessary intelligence expertise, particularly when a determination regarding violent extremism is needed.[123] He further explained:

Although the RCMP and [the Canadian Security Intelligence Service] are subject to fairly rigorous scrutiny by [the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency], the OPP and municipal forces, when they collect intelligence, are subject to very limited scrutiny, only by the Ontario independent police review director, if that person has enough resources to do systemic reviews. My understanding is that they don’t.[124]

Given the evidence received about intelligence and policing, the Committee therefore recommends:

Recommendation 8

That the federal government, in conjunction with Indigenous, provincial, and territorial governments; police and intelligence agencies; the Parliamentary Protective Service; the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police; and other stakeholders, develop or enhance protocols on information sharing, intelligence gathering, and distribution that:

- identify how and by whom information and intelligence should be collected, analyzed and distributed for major events, such as protests, that have multijurisdictional or national significance;

- enhance the ability to collaboratively evaluate information collected for reliability;

- adhere to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the reasonable expectations of privacy of those affected;

- enhance record-keeping regarding the collection, analysis and distribution of information and intelligence;

- ensure compliance with legislative mandates, for example, statutory limits on surveillance of lawful protests by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service;

- promote appropriate access to and interpretation of social media and open-source materials;

- ensure that, where appropriate, comprehensive, timely and reliable intelligence is communicated to police and government within their appropriate spheres of decision making; and

- promote objective, evidence-based risk assessments that are written to both acknowledge information deficits and avoid misinterpretation.

Recommendation 9

That the federal government, in conjunction with Indigenous, provincial, and territorial governments; police and intelligence agencies; the Parliamentary Protective Service; the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police; and other stakeholders, consider the creation of a single national intelligence coordinator for major events of a national, interprovincial or interterritorial dimension.

Cooperation Among Different Levels of Policing

Several witnesses testified about the different groups that were established to facilitate policing of the “Freedom Convoy,” and how these groups promoted teamwork and information-sharing among the OPS, OPP and RCMP, in concert with other partners.[125] These groups included the National Capital Region Command Centre (NCRCC), the Integrated Command Centre (ICC), the joint intelligence group, the joint planning cell, and Intersect.

The NCRCC included representatives from the RCMP, OPP, OPS, PPS, and the City of Ottawa, as well as “other law enforcement from the Quebec side, transport, ambulance technicians and firemen.”[126] Then Deputy Commissioner of Federal Policing, Michael Duheme of the RCMP, provided testimony to the Committee regarding the role of the NCRCC:

It’s just a coordination hub to make sure that everybody’s in tune with what’s going on […] [i]t’s more a coordination centre for information that comes in before we go into the operational mode […] That’s also used as a hub for intelligence that’s going on for the event.[127]

Created on 12 February 2022, the ICC was led by the OPS, and it included the OPP and the RCMP.[128] Its role was to review the plan in response to the “Freedom Convoy.”[129] Michael Duheme told the Committee how the ICC worked:

In the integrated command centre that we had, there were multiple law enforcement agencies there. At gold level, as it were, there was me, Deputy Commissioner Harkins from the OPP, as well as the interim chief of police, Mr. Bell.

Discussions were ongoing on the way forward. For every plan that was set forward, we were in agreement with the plan. It wasn’t necessarily a consensus, but everybody was in agreement as to how we were going to tackle this and the sequence of events as we moved forward.

The OPS is the one thing I want to make clear. OPS maintained the lead throughout this. Both the RCMP and the OPP were supportive throughout, but the joint command…. There were conversations as to the best way to proceed forward to address the situation.[130]

According to Brenda Lucki, the joint planning cell was created “specifically for the enforcement.”[131] Finally, Intersect was described by Steve Kanellakos as an intelligence group that was led by the OPS.[132]

Some witnesses reflected positively on the level of cooperation among the various police services involved.[133] Specifically, Peter Sloly credited the work of Commissioner Thomas Carrique of the OPP and his senior staff as “fundamental to the ultimate success of what took place in January and February.”[134] The sharing of resources by the OPP and RCMP with the OPS, and specifically the number of officers sent to assist in Ottawa, was also discussed by several witnesses.[135]

Other witnesses reflected less favourably on the cooperation between different levels of policing.[136] Jim Watson remarked that there was greater cooperation from the OPP and RCMP after the resignation of Peter Sloly.[137] Kent Roach described the various levels of policing were described as “fragmented and dysfunctional governance silos.”[138]

In a brief submitted to the Committee, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association summarized some of the findings of the Commission in relation to policing challenges, including that several witnesses testified that “the issue was not legal authority, but coordination, planning, and resource issues within and between police services.”[139]

In his appearance before the Committee in February 2024, Michael Duheme, now Commissioner of the RCMP, said that the use of additional police resources has evolved in the last two years following the declaration of a public order emergency, in that a call for assistance on Parliament Hill now goes first to the OPP, not the RCMP. The RCMP may later intervene to establish order on the Hill, at the request of the OPP, if necessary.[140] Michael Duheme added that, “[f]rom a law enforcement perspective, we are in a different place than we were when the convoy happened.”[141]

Before the invocation of the Emergencies Act, the Committee agrees that relevant police services should be meaningfully consulted by the federal government. This recommendation stems from evidence received by both the Commission and the Committee.

There is evidence to suggest that police leadership had not exhausted all available tools to bring the protests and blockades to their conclusion when the federal government decided to invoke the Emergencies Act. At the Commission, a 14 February 2022 email from Brenda Lucki to the chief of staff to former Minister Mendicino states that:

This said, I am of the view that we have not yet exhausted all available tools that are already available through the existing legislation. There are instances where charges could be laid under existing authorities for various Criminal Code offences occurring right now in the context of the protest. The Ontario Provincial Emergencies Act just enacted will also help in providing additional deterrent tools to our existing toolbox.

These existing tools are considered in our existing plans and will be used in due course as necessary.[142]

Brenda Lucki discussed this email during her testimony at the Commission on 15 November 2022.[143] Furthermore, according to an exhibit received by the Commission, Brenda Lucki was present at a 13 February Cabinet meeting but nothing in the minutes for that meeting indicates that she spoke at that meeting.[144]

Jody Thomas also discussed her consultations with Brenda Lucki at both the Commission and the Committee. Jody Thomas testified at the Commission that, at the Incident Response Group (IRG), individuals who attend IRG meeting “are expected to provide information that is of use to decision-makers, being the Prime Minister and his Cabinet.”[145] She also told the Commission that Brenda Lucki did not say anything specific as to whether law enforcement had exhausted all its tools.[146]

Jody Thomas told the Committee that she spoke to Brenda Lucki several times before 14 February 2022, and that she did not ask Brenda Lucki whether there were other means that could have been used other than invocation of the Emergencies Act.[147] She also commented that she did not read the operational plan prepared by the police services during the declaration of emergency.[148]

Furthermore, Peter Sloly told the Committee that the OPS had a plan ready to clear downtown Ottawa, and the OPS maintained control of the plan during his tenure as chief of police.[149]

Policing of the Parliamentary Precinct

Some witnesses testified regarding the special measures that were put in place to ensure safety on Parliament Hill during the “Freedom Convoy,” as part of the RCMP’s mandate to protect Parliament and parliamentarians.[150] Brenda Lucki described how both vehicular and protester access to Parliament Hill was restricted, and a staging area was provided by the RCMP where parliamentarians could meet and get driven to Parliament if they so wished.[151]

Several witnesses described challenges specific to maintaining safety within the Parliamentary Precinct during the protests in Ottawa. For example, Larry Brookson commented that, during the protests in Ottawa, he had concerns regarding the safety of parliamentarians crossing Wellington Street in Ottawa to enter the West Block.[152] Julie Lacroix, Director of Corporate Security at the Senate, alluded to challenges with technology and infrastructure, stating that, in the future, “I think my recommendation would be to ensure we have the necessary technology and infrastructure to allow us to close and secure the precinct when necessary.”[153] Larry Brookson and Patrick McDonell, Sergeant-at-Arms and Corporate Security Officer at the House of Commons, further underlined a lack of situational awareness as a critical concern throughout the protests in downtown Ottawa.[154]

Patrick McDonell also described the harassment experienced by parliamentary staff during the “Freedom Convoy” protests in Ottawa:

What was happening every day was that our employees were being harassed. […] We had employees pulling in and out of there every day. There was banging on the cars and there was a police cruiser within sight, a police cruiser witnessing it, and nobody exiting the police cruiser.[155]

Patrick McDonell explained that incidents of harassment of parliamentary staff were not policed by the OPS and had to be addressed by the PPS.[156]

Larry Brookson testified to the Committee that, approximately one week before the arrival of the “Freedom Convoy,” the PPS had recommended that vehicles not be permitted to park on Wellington Street, but the OPS permitted protesters to park their vehicles anyway, and that this decision compromised safety in the Parliamentary Precinct.[157] Jim Watson suggested that allowing protesters to use Parliament Hill as a backdrop may have contributed to the entrenched nature of the protests, describing how “[t]here’s nothing spectacular about the scenery on Slater and Albert [streets], and they probably wouldn’t stay that long [if Wellington had been closed].”[158]

Both Larry Brookson and Patrick McDonell recommended that the Parliamentary Precinct be extended to include parts of Wellington Street.[159] The Committee agrees, and therefore recommends:

Recommendation 10

That the Parliamentary Precinct be expanded to include Wellington Street; and that additional expansions to the Parliamentary Precinct be considered in consultation with the Parliamentary Protective Service, Ottawa Police Service, Ontario Provincial Police, and the federal, provincial and municipal governments.

Recommendation 11

That, in view of the above recommendation, the federal government give consideration to resource allocation for the Parliamentary Protective Service to secure an enlarged Parliamentary Precinct; and that Wellington Street be closed to vehicular traffic in order to further secure Parliament Hill for parliamentarians, visitors and residents of the area.

In relation to policing in the Parliamentary Precinct, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 12

That decisions concerning parliamentary security operations, and particularly in striking the right balance in ensuring the Parliament of Canada is safe and secure while remaining open and accessible to all, including those peacefully protesting, be the responsibility of security and policing professionals, and be subject to parliamentary oversight.

On the second anniversary of the declaration of a state of emergency, Shawn Tupper, Deputy Minister of Public Safety Canada, testified before the Committee that conversations were still ongoing concerning the Parliamentary Precinct regarding, one, how the Parliamentary Precinct and its boundaries are defined and, two, how the precinct is policed and maintained.[160]

Committee takes note that, in its response to the recommendations of the Commission’s report, the federal government stated that:

[It] reaffirms its commitment to continue discussions with the City of Ottawa to transfer a portion of Wellington Street to the federal government, with the goal of marking the legal and geographic boundaries of the Parliamentary Precinct, and clearly defining security and policing roles and responsibilities in the area.[161]

Chapter 6: National Security and the “Freedom Convoy”

There are several federal departments and agencies involved in national security and the collection and assessment of intelligence related to national security. Eight core federal organizations within Canada’s security and intelligence community have mandates related to national security, intelligence or both: the National Security and Intelligence Advisor, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), the Department of National Defence/Canadian Armed Forces, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), the Communications Security Establishment, the RCMP, Global Affairs Canada, and the Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre (ITAC).[162] There are nine other federal departments and agencies that are also involved in national security and intelligence, including the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC), Public Safety Canada and Justice Canada.[163] Most of these departments and agencies submitted institutional reports to the Commission in relation to their activities during the “Freedom Convoy.”[164]

Two types of national security threats came up during the Committee’s review of the exercise of powers and the performance of duties and functions pursuant to the declaration of emergency of February 2022: ideologically motivated violent extremism (IMVE) and threats to critical infrastructure.

IMVE, which can be distinguished from religiously motivated violent extremism and politically motivated violent extremism, “is often driven by a range of grievances and ideas from across the traditional ideological spectrum” and draws on “a personalized narrative which centres on an extremist’s willingness to incite, enable and or mobilize to violence.”[165] CSIS has identified four categories of IMVE, which are xenophobic violence, anti-authority violence, gender-driven violence and other grievance-driven and ideologically motivated violence.[166]

Critical infrastructure is defined by Public Safety Canada as:

[P]rocesses, systems, facilities, technologies, networks, assets and services essential to the health, safety, security or economic well-being of Canadians and the effective functioning of government. Critical infrastructure can be stand-alone or interconnected and interdependent within and across provinces, territories and national borders. Disruptions of critical infrastructure could result in catastrophic loss of life, adverse economic effects, and significant harm to public confidence.[167]

The National Strategy for Critical Infrastructure identifies 10 critical infrastructure sectors in Canada: energy and utilities; finance; food; transportation; government; information and communication technology; health; water; safety; and manufacturing.[168]

It should be noted here that the discussion with respect to “threats to national security” as it relates to the invocation of the Emergencies Act can be found in Chapter 7: Invocation of the Emergencies Act of this report.

On the subject of the federal government’s response to the national security threats during the “Freedom Convoy,” several witnesses described the role of the various federal departments and agencies that were involved in monitoring and assessing the situation. According to Jody Thomas, some of these organizations involved included CSIS, the RCMP, the Canadian Forces Intelligence Command, the foreign intelligence group of Global Affairs Canada, the CBSA, and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.[169]

David Vigneault, Director of CSIS, testified that, during the “Freedom Convoy,” CSIS used its investigative resources to monitor known threats and inform law enforcement partners and the government about the nature of developing national security threats.[170] In a second appearance before the Committee in February 2024, David Vigneault added that, in addition to sharing intelligence with law enforcement, CSIS worked closely with partners in the RCMP and CBSA, and that, depending on the situation, all three agencies took “specific operational measures” to respond to the situation.[171]

Marie-Hélène Chayer, Executive Director of ITAC, described her agency’s role in assessing the likelihood of a terrorism attack happening in Canada and overseas.[172] Finally, Jody Thomas testified that her role as National Security and Intelligence Advisor comprised providing coordinated, non-partisan advice to the Prime Minister, “coordinating the national security and intelligence community and providing a challenge function.”[173]

Barry MacKillop, Deputy Director of Intelligence at FINTRAC, explained that his agency was responsible for generating “actionable financial intelligence for Canada’s police, law enforcement and national security agencies.”[174] Barry MacKillop added that the Regulations and the Order did not change FINTRAC’s role with respect to its usual mandate and that they did not grant FINTRAC “any extended powers or enhanced authorities from a financial intelligence perspective.”[175]

With respect to the role of FINTRAC, in addition to the added utility applicable across all law enforcement, including beyond the application of the Emergencies Act, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 13

That the federal government review the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act to determine if the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada should be given any additional powers when there are “threats to the security of Canada” as defined by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act.

Some witnesses also referred to the joint intelligence group, which was established to share intelligence information throughout the “Freedom Convoy.” David Vigneault described how the joint intelligence group provided a forum for intelligence-sharing with law enforcement partners and to provide advice to the government on national security threats, while Brenda Lucki also referred to the joint intelligence group, stating that information was funnelled through it during the “Freedom Convoy.”[176]

One of the national security threats that was most often invoked by witnesses was IMVE. As Peter Sloly explained, the “Freedom Convoy” began as an anti-vaccine demonstration “and was co-opted by different ideologically radicalized individuals and insurgency movements.”[177] However, as Rob Stewart told the Committee, CSIS did not actually identify any specific IMVE threats, but the federal government was aware of the presence of extremists who were attempting to link their cause to the “Freedom Convoy.”[178] Brenda Lucki further confirmed that ideologically motivated extremists were likely present at the protests in Ottawa and were attempting to use the protest to promote their own ideological goals.[179]

Some witnesses discussed the role of social media and the Internet in disseminating IMVE and motivating individuals to act. Marie-Hélène Chayer explained that since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an increase in the amount of IMVE rhetoric online and on social media.[180] David Vigneault further explained that violent extremists have used protests and demonstrations in the past to engage in violence, recruit members and spread their ideology.[181] Jody Thomas also described the unprecedented number of serious and credible online threats against politicians and public officials of all three levels of government since the 2021 federal election.[182]

In a second appearance before the Committee in February 2024, David Vigneault added that the events of February 2022 are one example of how the threat facing Canada has become “more complex and more pervasive”[183] and that “violent extremism in our country, motivated both by ideology and by religious motives,”[184] has increased in the last two years following the declaration of a public order emergency.

Former Minister Blair described another type of threat to national security – threats against critical infrastructure – in terms of the disruption to manufacturing and transportation caused by the “Freedom Convoy,” and he explained how the disruptions to the points of entry constituted a “very significant threat to national security” because of the impact to critical infrastructure.[185] However, Leah West, Assistant Professor at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs at Carleton University, added that the current definition of a “public order emergency” in the Emergencies Act does not contemplate emergencies as a result of threats to critical infrastructure.[186]

Chapter 7: Invocation of the Emergencies Act

Section 16 of the Emergencies Act, which defines a “public order emergency,” provides for two main branches for determining whether the applicable legal threshold has been met for the invocation of a public order emergency. A “public order emergency” is defined as “an emergency that arises from threats to the security of Canada and that is so serious as to be a national emergency.” [Emphasis added][187] The first branch is that the public order emergency must arise from “threats to the security of Canada” as defined in section 2 of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act (CSIS Act).[188] The second branch is that there must be a “national emergency” within the meaning of section 3 of the Emergencies Act.

Section 2 of the CSIS Act defines a “threat to the security of Canada” as follows:

(a) espionage or sabotage that is against Canada or is detrimental to the interests of Canada or activities directed toward or in support of such espionage or sabotage,

(b) foreign influenced activities within or relating to Canada that are detrimental to the interests of Canada and are clandestine or deceptive or involve a threat to any person,

(c) activities within or relating to Canada directed toward or in support of the threat or use of acts of serious violence against persons or property for the purpose of achieving a political, religious or ideological objective within Canada or a foreign state, and

(d) activities directed toward undermining by covert unlawful acts, or directed toward or intended ultimately to lead to the destruction or overthrow by violence of, the constitutionally established system of government in Canada,

but does not include lawful advocacy, protest or dissent, unless carried on in conjunction with any of the activities referred to in paragraphs (a) to (d).

A “national emergency” is defined in section 3 of the Emergencies Act as:

an urgent and critical situation of a temporary nature that

(a) seriously endangers the lives, health or safety of Canadians and is of such proportions or nature as to exceed the capacity or authority of a province to deal with it, or

(b) seriously threatens the ability of the Government of Canada to preserve the sovereignty, security and territorial integrity of Canada

and that cannot be effectively dealt with under any other law of Canada.

It is important to note that the Emergencies Act specifies that the Governor in Council must believe “on reasonable grounds, that a public order emergency exists and necessitates the taking of special temporary measures for dealing with the emergency.”[189] As such, certainty that a public order emergency exists is not necessary under the Emergencies Act.

Volume 3 of the Commission’s report describes the “reasonable grounds to believe” standard and explains that:

Provided that the necessary factual basis exists, the “reasonable grounds to believe” standard builds in the concept of a margin of appreciation. Reasonable minds may differ on the same question, and a decision is not wrong or unreasonable because an outcome thought likely to happen does not materialize.[190]

The Commission’s report further elaborates that:

To return once again to the theoretical principles underlying emergency powers, the threshold for invocation is the point at which order breaks down and freedom cannot be secured or is seriously threatened. In my view, that threshold was reached here.

I do not come to this conclusion easily, as I do not consider the factual basis for it to be overwhelming and I acknowledge that there is significant strength to the arguments against reaching it. It may well be that serious violence might have been avoided, even without the declaration of emergency. That it might have been avoided does not, however, make the decision wrong. There was an objective basis for Cabinet’s belief, based on compelling and credible information. That was what was required. The standard of reasonable grounds to believe does not require certainty. [Author’s emphasis][191]

The public statement (delivered orally) on 17 February 2023 by Commissioner Paul S. Rouleau also addresses the importance of the standard of reasonable grounds in his findings:

After careful reflection, I have concluded that the very high threshold required for the invocation of the Act was met.

Specifically, for reasons that I present in detail in the report, I found that when the decision was made to invoke the Act on 14 February 2022, Cabinet had reasonable grounds to believe that there existed a national emergency arising from threats to the security of Canada that necessitated the taking of special temporary measures.

I did not come easily to this conclusion, because to me the underlying facts are not obvious. Thus, reasonable and informed people might come to a different conclusion from mine. I therefore reluctantly come to this conclusion. The government should normally be able to respond to emergencies without resorting to exceptional powers. [Author’s emphasis][192]

According to Ryan Alford’s brief to the Committee:

The evidence that demonstrated that the crisis did not satisfy either of these statutory and constitutional thresholds is extensive. That said, owing to the deferential standard the inquiry must apply, it is possible that the Final Report of the Rouleau Commission may conclude that it is impossible to determine with the requisite certainty whether the Government had a reasonable basis to conclude that a public order emergency existed. [Author’s emphasis][193]

Leah West also testified that:

I think the Emergencies Act has incredible amounts of discretion for the executive, and that would be how anyone would interpret it: whether or not they had reasonable grounds to believe a threat to the security of Canada existed and then whether it was necessary. They have incredible amounts of discretion there, but when Parliament has chosen to be very narrow—in this case, in its use and the definition of threats to the security of Canada—it's important that be respected because it was a deliberate choice, and the rule of law is the backbone of what makes us a liberal democracy that thrives on the rule of law. [Author’s emphasis][194]

In response to Leah West, Kent Roach added that:

I agree with Professor West that you need to have paragraph 2(c), plus section 3, but then subsection 17(1) says, “When the Governor in Council believes, on reasonable grounds, that a public order emergency exists and necessitates the taking of special temporary measures”. It seems to me that the issue for cabinet, and the issue that may be explored in that legal opinion, is whether they have reasonable grounds to believe that a public order emergency exists. [Author’s emphasis][195]

This was also discussed before the Commission by Professor Robert Diab of the Thompson Rivers University Faculty of Law and Morris Rosenberg, former Deputy Minister of Justice and Deputy Attorney General of Canada, as well as former Deputy Minister of Health and Foreign Affairs. Robert Diab told the Commission:

So the way it works right now in the Emergencies Act is that the decision maker is the federal government. It must decide whether it thinks the standard is met, and then the Commission is the after-the-fact referee.

But I think if we had ordinary legislation, maybe the model would be something like a warrant, where you have an independent decision maker. [Author’s emphasis][196]

Morris Rosenberg also told the Commission:

The government's required to believe on reasonable grounds that a public order emergency exists and necessitates the taking of special temporary measures for dealing with it. That judgment is subject to judicial review by the courts and subject to review by Parliament and by the inquiry that's established after the emergency is over. All three of those accountability mechanisms should require the government to clearly explain whether were other laws that, on their face, could have been used and why they were rejected. [Author’s emphasis][197]

The question of whether the legal threshold for invoking the Emergencies Act was met was discussed at length not only at the Committee, but also at the Commission. At the Commission, David Vigneault testified that CSIS did not consider the protests against the public health measures and the activities undertaken by protesters as a threat to the security of Canada, and they were not investigated by CSIS as such.[198] However, the protests were considered to be an activity with the potential to become a threat.[199]

In response, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau explained to the Commission that, for the purposes of the Emergencies Act, Cabinet, not CSIS, was responsible for determining whether there was a threat to the security of Canada as defined by the CSIS Act.[200] In making that determination, the prime minister told the Commission that Cabinet considered more than just the “inputs” provided by CSIS. Rather, inputs from the RCMP; Transport Canada; Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; the Clerk of the Privy Council; the National Security and Intelligence Advisor and the “whole of government” were considered when the federal government invoked the Emergencies Act in February 2022.[201]

Along the same vein, Jody Thomas told the Commission that, in her view, the Emergencies Act allowed for Cabinet to consider more than just the intelligence collected by CSIS in making its decision to invoke the Emergencies Act.[202]

Justification

Some witnesses before the Committee cited the public safety concerns as justification for Cabinet’s decision to invoke the Emergencies Act. For instance, former Minister Mendicino told the Committee that the federal government received advice “that law enforcement needed the Emergencies Act to be sure that they could resolve, for example, ambiguities around those who were staying close to ports of entry.”[203] He reiterated that “we invoked the Act because it was the advice of non-partisan professional law enforcement that existing authorities were ineffective at the time to restore public safety.”[204] Former Minister Blair similarly testified that law enforcement required additional authorities.[205] Jody Thomas specifically cited concerns about weapons and IMVE as justification for Cabinet’s decision to invoke the Emergencies Act.[206]